2020 vision

Dalton — The S&P 500 stock market index will hit 3,264 points in 2020. Or, at least, that’s the average vision of Wall Street analysts. That’s an increase of about 3 percent from last week’s highs. MarketWatch surveyed some of Wall Street’s “top strategists” (whatever that means) to get their view on how the stock index would perform next year. There was a range of views with a few expectations in the 3,400 range (about an 8 percent gain from last week’s levels) and a couple targets of 3,000 (about a 5 percent loss from last week’s levels). For calendar year 2020, analysts are projecting earnings growth of 9.9 percent and revenue growth of 5.5 percent. If the stock market followed earnings growth perfectly, that theoretically would be enough to get the index above that high target of 3,400 points (don’t try too hard to make the math work on the guesstimates of Wall Street analysts).

Given the expectation of about $175 per aggregate S&P 500 share, the forward price-to-earnings (or P/E) ratio (a measure comparing the price of something relative to its next 12 months of earnings) of the S&P 500 is almost 18. That is above the five-year average of 16.6 and above the 10-year average of 14.9. According to the popular P/E ratio metric, the stock market is mildly expensive.

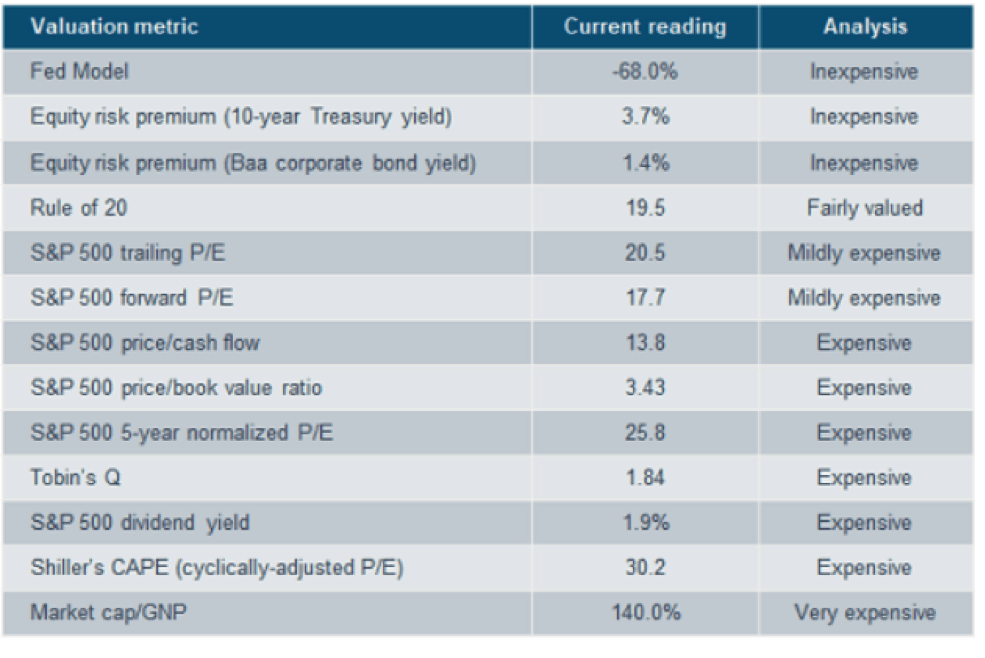

If the companies in the S&P 500 do aggregately earn $175 per share, but the index tracks back to that average 14.9 P/E ratio, that translates to a stock market crash of 17.5 percent. Whether the Wall Streeters expect 3,400 or 3,000 on the S&P 500, the math suggests that they’re being rather aggressive if you look at it through the lens of P/E ratios. Though, in fairness, with interest rates so low, one could argue for a 17-ish P/E, and at $175 of earnings, which translates closer to 3,000 on the S&P 500, a mere 5 percent loss. While the most popular, admittedly, the P/E ratio is only one valuation tool. Above is a list of other valuation metrics and their assessment of the market’s attractiveness. I am purposely going to spare you the definition of these so that you can focus on the fact that while the stock market is more overvalued than undervalued, it’s not a clear-cut sell based on valuations alone. An expensive market can keep getting more expensive. Or, if we’re luckier, fundamentals can catch up to prices.

What do I think the level of the S&P 500 will be Dec. 31, 2020? I have no clue, and neither do the Wall Street strategists. I’m not being self-deprecating; I’m bashing the traditional annual “obligation” of setting stock market targets. Let me explain. I’m not one of those financial advisor weirdos who will tell you that returns don’t matter, because they do. It matters very much if we expect stocks to go up or down, and by how much. But to set a specific price target for a specific day is just playing into some sort of ludicrous expectation that is set either by the advisors’ firm or their clients or both. In the past, when I’ve played a version of this game, I’ve focused more on the direction of fair value. And I’ve never set a specific date, because that’s a stupid guessing game. I’d give a price range that could be nudged up or down due to selling out of fear or buying out of greed, pushing an index’s price level away from fair value. Also, I’d argue that instead of 12 months out, we’re looking nine to 15 months out. The market is going to move slower or faster toward fair value for a whole host of reasons, and to think it’ll get there on some exact day is just dumb.

I calculate fair value to be about 20 percent lower than where we are today. But I’m not so naive to think that the stock market will act rationally and necessarily drop to those levels. Stock prices generally overreact to the upside as well as to the downside. There is a difference between me thinking what the market should do, and what I think the market will do. I think it should adjust downward, a lot, and reach a fair valuation. But I think the U.S. trade war with China will affect the stock market less negatively than it has and, despite all the recessionary warnings out there, things will get a bit better, probably allowing the market to advance about 4-7 percent in 2020 (give or take a few months), possibly after it goes negative in the beginning of the year as it simultaneously digests what appears to be a blow-off top and the consideration of who will be the Democratic presidential nominee.

Switching indices, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was up 10.5% over the course of 74 trading days, from Mid-August to late November. According to a Dec. 4 report from Ned Davis Research, and as reported on CNBC, NDR noted that blow-off tops had a median gain of 13.4 percent over a median time frame of 61 days, dating back to 1901. That’s not to say the stock market is ready to crash — yet. After all, although stocks have had an amazing 2019, the S&P 500 is only up 7.4 percent over the last 15 months. Year-to-date we’ve had three corrections in the 4 percent to 7 percent range, each correction lasting about a month. I’m not trying to call the timing of the next 4 percent to 7 percent correction, because I just don’t care. (Well, and because I’m not that good.) Those things come and go. My bigger concern will be just how much the stock market might crash between the Feb. 3, 2020, presidential caucuses and the presidential election. I emphasize “might.” The good news is that, according to the Stock Trader’s Almanac, since 1952, the stock market, as measured by the DJIA, rises an average of 10.1 percent during election years when a sitting president runs for re-election, compared to a drop of 1.6 percent during election years when there is an open field. The stock market has only been negative in four of the 23 election years sine 1928. And the worst quarter of a presidential election year, on average, only experiences about a 1.5 percent loss. I say there “might” be a crash because, just as you can’t rely on past performance on the upside, you can’t rely on past performance to protect you from the downside. A new president could radically change the tax structure of the corporations you invest in just at the same time whispers about an economic recession might jump from the pages of Capital Ideas to the headlines of main street news.

But for now, stay invested. Despite arguing over the details of the so-called “Phase I” trade truce, the tone of the U.S.-China conversations has improved. Also, though still numerous, the signs of a 2020 recession are fewer than a few months ago, and we may get out of next year with yet just another miniature slowdown. The real trouble, if any, is still a bit ahead of us. We’ll worry more about adding some insurance to your portfolio in the months to come.

–––––––––––––

Allen Harris, the author of ‘Build It, Sell It, Profit: Taking Care of Business Today to Get Top Dollar When You Retire,’ is a Certified Value Growth Advisor and Certified Exit Planning Advisor for business owners. He is the owner of Berkshire Money Management in Dalton, managing investments of more than $400 million. His forecasts and opinions are purely his own. None of the information presented here should be construed as individualized investment advice, an endorsement of Berkshire Money Management or a solicitation to become a client of Berkshire Money Management. Direct inquiries to [email protected].

This article originally appeared in The Berkshire Edge on December 11, 2019.

Allen is the CEO and Chief Investment Officer at Berkshire Money Management and the author of Don’t Run Out of Money in Retirement: How to Increase Income, Reduce Taxes, and Keep More of What is Yours. Over the years, he has helped hundreds of families achieve their “why” in good times and bad.

As a Certified Exit Planning Advisor, Certified Value Builder, Certified Value Growth Advisor, and Certified Business Valuation Specialist, Allen guides business owners through the process of growing and selling or transferring their established companies. Allen writes about business strategy in the Berkshire Eagle and at 10001hours.com.