You’re Not as Rich as You Think You Are

“If you have a tax preparer, you do not have a tax planner.” —James Pollard’s CPA

“Tax preparation is focused on getting this year’s tax return prepared and to the IRS … it’s all about what happened this last year. Let’s get it done and move on … the contrast to that in tax planning is taking a forward-looking approach to saying, ‘what can we proactively do to make sure that we’re minimizing how much we have to pay to the IRS?’” —Steven Jarvis, CPA

I recently listened to James Pollard’s “Advisor Coach” podcast with guest Steven Jarvis, CPA. Non-industry folks won’t recognize those names. Still, I wanted to give proper attribution to the pair that inspired this week’s column. I know other financial advisors read my columns, so I want to help them help you.

Sometimes when you listen to podcasts, you learn new things (which I did), and sometimes you have your convictions confirmed (which also happened). My substantiated view is that … you’re not as rich as you think you are.

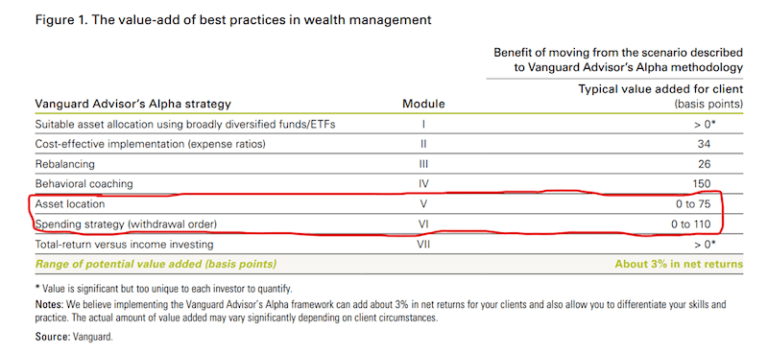

I am not just talking about the extra growth your investment portfolio could achieve if you held certain securities in particular accounts. According to The Vanguard Group, depending on your account types, proper asset allocation could gain you an additional 0.75% of return per year.

Withdrawing assets in the correct order (aka, your spending strategy) could gain you an additional 1.10% of return per year. PricewaterhouseCoopers and Morningstar corroborate similar findings – proper tax considerations could be worth almost 2% more per year to your portfolio’s growth. (Where you fall in those ranges of value depends on things like your ratio of taxable accounts to tax-deferred).

Investments with growth potential and low dividend payouts should be placed in taxable accounts. Conversely, some bonds and high dividend payers can go into tax-deferred accounts. If you use actively managed mutual funds, they should be placed in tax-deferred accounts to shield you from year-end fund distributions. And if you invest in individual stocks, I hope you aren’t paying someone for that. There are dozens of studies showing how stock pickers routinely underperform their benchmarks. Is it worth paying someone to take on more risk without providing the additional return? It seems as if investing in a tax-efficient manner is a superior strategy.

But there is more to it than your gains. It’s also about keeping what you have. Suppose you have a $2 million investment portfolio, evenly split between a taxable trust account and a tax-deferred account (such as an IRA or a 401k). When you take money from the taxable account, you must pay capital gains tax. So you only have about $800,000, not $1 million. And when you take money from the tax-deferred accounts, you’ll have to pay ordinary income taxes. Let’s be conservative and say the tax rate is 25%. You only have $750,000, not $1 million.

You don’t have $2 million – you have $1,550,000 and a $450,000 deferred tax liability.

You want to be tax-efficient with your investments because you’ll make more money. And you want to be tax-efficient when your money is on the way out, because you’ll keep more money.

Many people hold onto the money in their IRA until their early 70s, when they must then take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). If they need money, they take it from their trust account. The assets in the trust account are taxed at the capital gains rate (up to 20% for wealthier investors). And the IRA distributions will be taxed at the ordinary income rate, which is often higher for affluent investors. But it’s not as simple as that.

By the time you start pulling money from your IRA, it could be big enough that your distributions will be taxed at much higher rates. Plus, those distributions could cause some of your Social Security payments to be taxable. A solution could be to withdraw relatively small amounts from your IRA earlier to keep distributions taxed at the lowest rate possible. The Federal income tax brackets for 2021 are 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%. The goal is to funnel as many distributions as possible through the lowest rates. You don’t want to be in your 70s and bump yourself from the 12% bracket to the 24% bracket. Or, if you are a higher earner, from 24% to 35%.

You could also talk to your financial advisor about converting your IRA to a Roth IRA. You can withdraw from Roth IRAs tax-free, but there’s a cost to claiming that benefit. When you contribute to a Roth IRA, you are not allowed the tax deduction, as you can when you contribute to a traditional IRA. When you convert from an IRA to a Roth IRA, you’ll have to pay income taxes on the amount converted to make up for those deductions you previously took. Your advisor may find it beneficial to convert if you’ll be in a higher tax bracket when you withdraw the money. Or maybe the stock market crashed, and you can take advantage of temporarily suppressed asset levels. Or perhaps you want to leave your heirs an income-free tax asset, which may be more like family planning than tax planning.

For those who are philanthropically inclined, you can reduce or entirely satisfy your RMD by giving the distributions to a qualified charitable distribution (QCD). Donations to QCDs count toward RDMs but are not taxable. (No, you cannot also claim the QCD as a charitable deduction, but nice try). And, of course, you can harvest losses in your taxable accounts to offset against gains and some income.

Some investors only look at returns. They don’t look at the fees and they don’t take into consideration the hundreds of thousands — or millions — of dollars that can be lost to taxes. It’s not a smart idea to let taxes be the primary driver of your investment strategy. You should start with investments that are good for you, then perform tax planning around those securities. Managing the taxes you pay doesn’t have to be complicated, but it should be planned.

Taming the Temper Tantrum

Last week, I noted that, according to Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, I was wrong to think the U.S. economy had made enough “substantial progress.” The Fed had stated they need to see substantial progress before tightening monetary policy by tapering the amount of bonds the Fed is buying. (“Tapering” is the Fed’s preferred nomenclature for reducing bond purchases.)

The Fed is currently buying $120 billion of bonds, namely Treasuries and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS). This process is called quantitative easing, or QE. As I pointed out, the ceasing of QE is important to investors because many of us remember the 2013 “taper tantrums” of the stock market. A taper tantrum is a stock market selloff in response to easing QE.

As I noted in my last column, three Fed presidents agreed with me that tapering the bond purchase would come sooner, not later. Last week, Fed Governor Christopher Waller joined the “sooner, not later’ crowd. Referring to job growth, Mr. Waller said, “that’s substantial growth, and I think you could be ready to make an announcement [on bond purchase tapering] in September.” With a tapering announcement (but not necessarily actual tapering) coming as soon as next month, a stock market historian might be nervous right about now.

However, I don’t care anymore. I delved into the details of the Federal Reserve’s most recent meeting and came to that conclusion. I had the information a few hours before submitting last week’s article, but this is complicated and geeky stuff. I will do my best to explain it at the “you get the gist,” 29,000-foot level. At the 30,000-foot level, I see this as stock market insurance against a Fed policy misstep. This means I will hold my stock positions a bit longer.

The Fed established a new repo facility (to keep it simple, a “repo facility” is where investors can buy and finance purchases). This repo facility gives banks a place at the Fed to park their cash and earn a higher return.

Suppose the Fed begins tapering. They want to avoid a taper tantrum. So, the Fed allows banks to borrow money super cheaply from this new repo facility, then turn right around and buy higher-yielding Treasuries and MBSs. The Fed is giving banks a way to earn more money on their cash while simultaneously keeping the liquidity in the system. The stock market – and bank stocks in particular – just got more interesting.

Allen Harris is the owner of Berkshire Money Management in Dalton, Mass., managing investments of more than $700 million. Unless specifically identified as original research or data-gathering, some or all of the data cited is attributable to third-party sources. Unless stated otherwise, any mention of specific securities or investments is for illustrative purposes only. Adviser’s clients may or may not hold the securities discussed in their portfolios. Adviser makes no representations that any of the securities discussed have been or will be profitable. Full disclosures. Direct inquiries: aharris@berkshiremm.com.

This article originally appeared in The Berkshire Edge on August 9, 2021.

Allen is the CEO and Chief Investment Officer at Berkshire Money Management and the author of Don’t Run Out of Money in Retirement: How to Increase Income, Reduce Taxes, and Keep More of What is Yours. Over the years, he has helped hundreds of families achieve their “why” in good times and bad.

As a Certified Exit Planning Advisor, Certified Value Builder, Certified Value Growth Advisor, and Certified Business Valuation Specialist, Allen guides business owners through the process of growing and selling or transferring their established companies. Allen writes about business strategy in the Berkshire Eagle and at 10001hours.com.