When the chips are down

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” —attributed to John Maynard Keynes

In my November 22, 2021 column, I argued that supply chain issues will ease by August 2022. On November 24, 2021 — two days later — the World Health Organization first reported the Omicron variant of COVID-19. As of January 24, 2022, the seven-day average for newly reported COVID-19 deaths reached 2,191 a day, up from about 1,000 two months ago, before Omicron was first detected. That data is provided by Johns Hopkins University. According to the Centers for Disease Contril, nearly every new COVID-19 infection is now the Omicron variant.

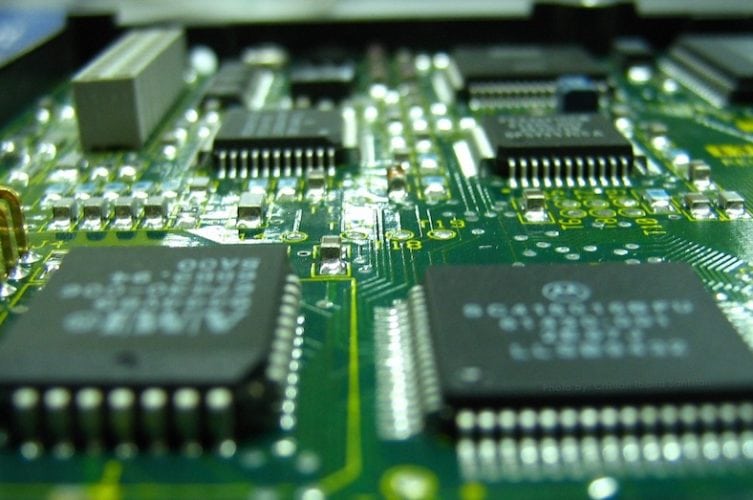

The facts changed. They changed for our health, and they changed when it comes to semiconductor chips. Semiconductor chips are necessary components in many of the technology products we use: cars, healthcare products, heavy machinery, toys.

On Tuesday, Jan. 25, 2022, the Commerce Department warned that U.S. manufacturers and other companies that use semiconductors are down to less than five days of inventory. That compares to 40 days of inventory held by companies before the pandemic.

The current chip inventory is down for all the reasons I discussed in the November 22, 2021 column. Depending on the type of chip, pre-pandemic it took 84–182 days to manufacture. By late 2021, even before Omicron, some of those times had doubled, with the manufacturing time stretched to 103–365 days. It appeared as if non-COVID-19 issues were close to peaking. Then shortages became further exacerbated due to overseas semiconductor manufacturing facilities having to shut down because of the rapidly spreading Omicron variant.

Overseas issues are important because so much of the chip production occurs outside of the United States. The good news is that chip companies have announced nearly $80 billion of new investments to be made in the U.S. The bad news is that those companies won’t see significant output until 2025. By then, the supply chains will have been fixed even without those U.S.-based investments.

Overall, the easing of the supply chain issues will be delayed by a few months due to Omicron. However, the shortage won’t clear up solely due to better vaccines and medical treatments. Better health will increase the supply side of the inflation equation, as will improvements in shipping products. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve will do what it must to slow the demand side of the inflation equation. (Inflation, at its basest, is too much money chasing too few goods.)

For semiconductors specifically, predicting the end of the supply chain issues is more difficult because so much of the manufacturing is done in foreign nations. That’s not an issue by itself, but forecasting the spread rate of and response to COVID-19 variants overseas is more complicated than I’d like to admit.

The significant shortage of chips means a low supply of lots of things at a time when U.S. consumers have purchasing power and demand for those lots of things. Inflation will persist. That means the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates to slow the economy to stave off inflation. This means more stock market volatility and much lower returns than some of us have become accustomed to for the last 22 months (January 2022 notwithstanding). I’ve predicted this before, and the Fed recently confirmed it.

The Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) met Wednesday, Jan. 26, 2022. The FOMC sets interest rate policy and decides how to best support its dual mandate of fostering economic conditions that achieve maximum sustainable employment and stable prices. The FOMC last met December 15, 2021. In the most recent statement, the FOMC removed the following text: “The Federal Reserve is committed to using its full range of tools to support the U.S. economy…”

The most recent FOMC statement also:

- Shifted from describing inflation as “exceeding” its inflation rate target of 2 percent to “well above”

- Explained that it would be appropriate to raise interest rates when “labor markets reached maximum employment” to “soon” (implying the March 15–16 meeting).

The Fed is going to take inflation seriously. Investors may not want that, but much of America does.

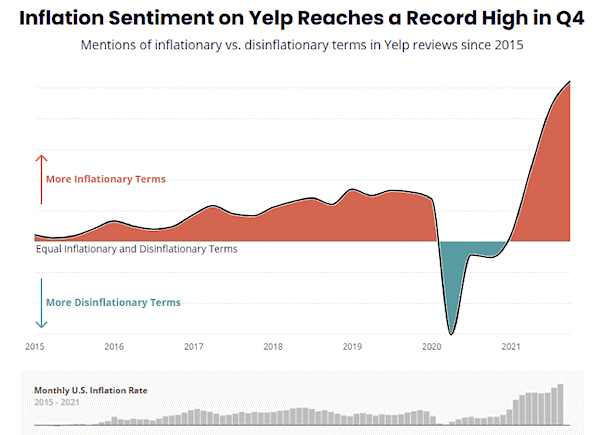

According to Yelp’s recently released 2021 report, consumer concerns about inflation reached a record high. (Yelp is an online consumer-to-business ranking and commentary website.) Yelp reviewed consumer language that pertained to inflationary experiences and compared those to terms that described disinflationary experiences. There was a surge of inflationary mentions in 2022.

The report also found that inflation is a concern for businesses. Almost all are paying more for all essentials … when they can find them.

Throughout the last nine months, I’ve shared with you my portfolio changes anticipating this shift by the Fed. I don’t know when the next investment moves will be, but I suspect there will be more. Stay tuned.

Allen Harris is the owner of Berkshire Money Management in Dalton, Massachusetts, managing investments of more than $800 million. Unless specifically identified as original research or data-gathering, some or all of the data cited is attributable to third-party sources. Unless stated otherwise, any mention of specific securities or investments is for illustrative purposes only. Adviser’s clients may or may not hold the securities discussed in their portfolios. Adviser makes no representations that any of the securities discussed have been or will be profitable. Full disclosures. Direct inquiries: [email protected].

This column appeared originally in The Berkshire Edge on January 31, 2022.

Allen is the CEO and Chief Investment Officer at Berkshire Money Management and the author of Don’t Run Out of Money in Retirement: How to Increase Income, Reduce Taxes, and Keep More of What is Yours. Over the years, he has helped hundreds of families achieve their “why” in good times and bad.

As a Certified Exit Planning Advisor, Certified Value Builder, Certified Value Growth Advisor, and Certified Business Valuation Specialist, Allen guides business owners through the process of growing and selling or transferring their established companies. Allen writes about business strategy in the Berkshire Eagle and at 10001hours.com.