What is in the Stimulus Package?

Well, I got that one wrong. Fortunately. Yes, we got a stimulus package!

I had said on November 30 that, “I am investing as if we’ll see something in the range of a $500 billion stimulus package announced by early February. (For comparison, JP Morgan is expecting a $1 trillion stimulus in March 2021.)”

Fortunately, what that has meant for me is that I had been targeting a full allocation of equities for my growth-oriented portfolios. On December 27, 2020, President Trump signed into law the $908 billion COVID-19 relief bill. That is good news for the economy and should support an overextended stock market (for a little while longer, anyhow.)

The new COVID-19 relief package includes, in part:

- A $300 per week federal unemployment supplement through mid-March. The package allows freelancers and gig workers to be eligible for benefits.

- Payments of $600 to individuals who earn up to $75,000 and couples filing jointly that make up to $150,000. The bill adds another $600 for every child. Those earning more than $75,000, but less than $99,000, will receive smaller checks.

- $284 billion into the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) for small business loans. Eligibility was expanded to new sectors, and the most beleaguered sectors will receive special consideration.

- $68 billion for vaccine distribution, including $20 billion to ensure Americans receive shots for free.

- $20 billion for COVID-19 testing and contact tracing.

- The bill extends the federal eviction moratorium through January 31 and funds $25 billion of rental assistance.

- $13 billion to food aid to increase the maximum Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefit by 15%.

- $82 billion into education, $45 billion into transportation, and $160 billion for state and local governments.

- $16 billion in payroll support for U.S. air carriers. The additional funding requires airlines to call back the 32,000 workers they furloughed this fall and keep employees on payroll through the end of March.

I breathed a sigh of relief (pun intended) after this package was signed. While I admit to having been invested bullishly, I was uneasy about a stock market that had gone too far, too fast. I am still nervous, just less so now.

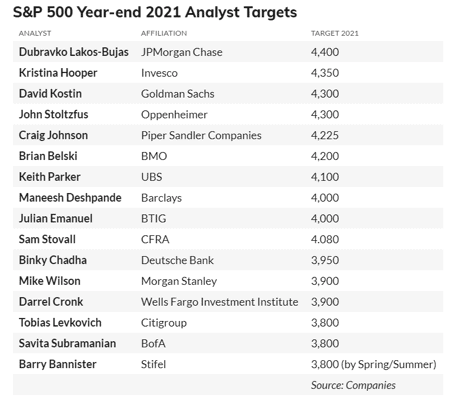

I assume the head analysts of Wall Street’s biggest firms also felt relieved. I have a spreadsheet of analyst prognostications as to what level the S&P 500 will reach next year (as I write this column, the index is at about 3,700 points). Half of the predictions are of returns of roughly 10%, or more, in 2021. That is a return expectation greater than 40% higher that of the long-term average return for the stock market. I consider that to be somewhat optimistic.

I am sure someone has negative expectations for the market in 2021. They’re just not on the list I have. And the list includes the “who’s who” of Wall Street forecasters.

Of the people on that list, I listen most closely to Sam Stovall of CFRA and Tobias Levkovich of Citigroup, both of whom have predictions in the bottom third of return expectations.

I’m not going to pretend to know where the market will be on some arbitrary date. I create a blueprint of what will happen, then BAM!, something happens, and new variables are added to the equation. There is continuously updated information to consider, so it doesn’t make that much sense (to me) to make a one-time assessment of prices twelve months hence.

The stock market is overvalued. It is overbought. I can come up with a dozen reasons why the stock market should go down. The first few months of 2021 should be awful. The pandemic is intensifying, and that will continue to force business restrictions. Nonetheless, Wall Street analysts are bullish. Too bullish for a contrarian like myself.

And many financial advisors are also too bullish. According to Investors Intelligence, the U.S. Advisors Sentiment survey has been near the “danger” level for months. Households are extremely bullish, as well. According to the American Association of Individual Investors (AAII), the number of bullish people is nearly 15% higher than its historical average. As fellow market contrarians will point out, that type of over-optimism creates challenges for stock prices.

An argument can be made that there is a trillion dollars, maybe two, sitting in money market mutual funds, just waiting to find its way into stocks. That could lift the stock market by about 5%. But I am less concerned about buying and more worried about selling. Many investors have been lured into the market due to the fear of missing out (FOMO). These FOMO traders aren’t buying stocks because they know what they are doing. They are buying stocks because the stock prices have been going up. These FOMO traders expect that what is happening will continue to occur. I once heard someone refer to that expectation as “forecasting for dummies.”

Serious investors will rebalance their portfolios back to their target allocations if those allocations have gotten out of line. Rebalancing could mean the sale of some high-flying stocks, which would put pressure on their prices. Less sophisticated sellers might respond by selling their shares because these FOMO investors will expect that what is happening will continue to occur. So long as any stock market sell-offs occur because of flaky investors and not due to renewed economic headwinds, I’ll feel okay remaining mostly invested in equities.

A sell-off in some high-flying names doesn’t typically bring down the market. Over more extended periods, rotation from one sector to another can be supportive of broader markets. A rotation can allow some sectors to make up lost ground as others have time for earnings to catch up to prices. Sometimes. But this time, rotation into value-oriented industries and away from the high-flying U.S. technology sector might bring the market down.

Technology’s weight in the S&P 500 is nearly 28% of the index’s capitalization. That is 10 percentage points higher than its historical average since 1990. If technology stocks get into trouble, it’s unlikely that higher prices of stocks in industries such as financial services (10.3% of the index) or industrials (8.5%) will be enough to maintain the pace of stock market gains we’ve enjoyed for the last nine months.

On the other hand, we have $908 billion of new stimulus, which should be enough to keep the U.S. economy from dipping back into recession. And efficacious COVID-19 vaccines are being distributed. Social gathering restrictions will be lifted, and economic activity should be robust. There is a lot of pent-up demand by households to visit their favorite restaurants, get on a plane again, and attend concerts and ball games. Furthermore, the economy will enjoy a large, albeit temporary, boost from restocking depleted inventories.

Additionally, the traditional headwinds that stifle market gains — rising interest rates and high oil prices — are not currently an issue. Oil prices are off their highs. And the Federal Reserve has adopted a “whatever it takes” attitude toward supporting growth. Also, equities have historically rallied under Democratic presidents. Since 1928, the first year of a Democratic president’s tenure has experienced a median gain of 9.6%. Oh, and let’s not forget that the S&P 500 took out its prior high after a significant drawdown. When this has happened in previous bull markets, the S&P 500 has experienced a median gain of 38% over 26 months.

I am concerned, but I am hesitant to stop riding this wave.

My concerns for U.S. equity markets are augmented because any proceeds from the sale of high-flying stocks may not be reinvested into other U.S. stocks. I speculate that some proceeds might be reinvested into foreign equities.

Emerging Market (EM) stocks look attractive with valuations that are 15% cheaper than their average discounts to developed markets. If there is a rotation from high-beta technology stocks, the proceeds may not chase the usual suspects like consumer staples or utility stocks. Economic growth worldwide allows investors to switch from a “risk-on” trade to some other risk-on trade (instead of moving from risk-on to risk-off). Instead of rotating from tech to real estate investment trusts (REITS), for example, I suspect more proceeds to find their way to EM. A vaccine-driven global recovery will demand exports from emerging markets.

In mid-November, I announced that I was exploring EM. I took a small (3%) position in Chinese equities by investing in the iShares China Large-Cap ETF (symbol: FXI). Then, a couple of weeks ago, I began to detail my growing interest in broadening EM exposure.

Although it’s barely been a month, FXI has struggled to keep its head above water. Considering the benefit of taking advantage of some tax-loss selling in 2020, I sold FXI last week. I swapped it into the Innovator MSCI EM Power Buffer ETF (symbol: EJAN). EJAN seeks to track the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, with a predetermined cap of almost 14%, while buffering investors from the first 15% of losses over the 2021 calendar-year outcome period. You can find information on and the prospectus to EJAN here.

This column originally appeared in The Berkshire Edge on January 4, 2021.

––––––––––––––––––––––

Allen Harris is the author of ‘Build It, Sell It, Profit: Taking Care of Business Today to Get Top Dollar When You Retire,’ as well as the owner of Berkshire Money Management in Dalton, managing investments of more than $500 million. Unless specifically identified as original research or data-gathering, some or all of the data cited is attributable to third-party sources. Full disclosures: https://berkshiremm.com/capital-ideas-disclosures/. Direct inquiries to [email protected].

Allen is the CEO and Chief Investment Officer at Berkshire Money Management and the author of Don’t Run Out of Money in Retirement: How to Increase Income, Reduce Taxes, and Keep More of What is Yours. Over the years, he has helped hundreds of families achieve their “why” in good times and bad.

As a Certified Exit Planning Advisor, Certified Value Builder, Certified Value Growth Advisor, and Certified Business Valuation Specialist, Allen guides business owners through the process of growing and selling or transferring their established companies. Allen writes about business strategy in the Berkshire Eagle and at 10001hours.com.