Smarter than the average bear

Dalton — Many of us think that we’re somehow smarter than the next person. For example, typically 90% of respondents surveyed respond that they are better than the average driver, and that they are also better than average at getting along with people. It’s statistically impossible for 90% of people to be better than average. Overconfidence can be a healthy attribute. It makes us feel good about ourselves, which creates a positive framework. However, overconfidence in our investment skills can get us into trouble.

For example, in one study, 74% of mutual fund investors expected their investments to consistently outperform the stock market. But since the stock market is all of us collectively, the average investor is only going to experience market rate returns over the long term. In the shorter term, in any given calendar year, 80% of professional mutual fund managers fail to beat their benchmark. And its random as to who beats the market; there is no real consistency. Yet those investors still expect to be better than average.

There is that slim possibility of being better than average that keeps hope alive, and that hope breeds overconfidence. Overconfidence leads investors to believe that they will be one of the few who succeed. It turns out that people who trade the most, presumably due to misplaced confidence, produce the lowest returns. If anyone deserves to be confident, it’s the members of Mensa, a high-IQ society. Mensa has an investment club. In June 2001 it shared that its club returned just 2.5% percent over the previous 15 years, underperforming the market by 13% per year. It turned out that the club members were very good-natured about their failings, so I’m not trying to throw darts in their direction, especially since they came to realize that the overconfidence in their superior intellectual skills could not be translated to superior investment returns, and that can be a lesson learned for all of us.

The solution to overconfidence isn’t to suffer from the analysis paralysis caused from over-researching, or somehow instead feel inadequate. Just be humble. Recognize that your investment thesis might be the wrong one and don’t fall in love with it. Here’s the thing: Everything I’ve shared with you in this column I’ve been confident about. I’m happy I’ve been right so far. So far. But let’s consider that there are other people in the financial industry who are also confident about their predictions, but they vary from mine. Who do you believe: me or them? Well, of course I’m going to say me, because I’m a better-than-average driver and I get along well with people. The good news may be that you can believe me and most of the others. I spent last week in San Diego at the Schwab Impact investment conference with about 5,000 other people. What I found from speaking with my colleagues is that my assessment that a recession will start next year is largely supported. Additionally, Schwab backed this view as it released the results of its latest Independent Advisor Outlook Study, which was conducted Sept. 9-23, of 942 independent advisors, representing a total of $366 billion of assets under management.

I am not “all in” on a recession occurring over the next 12 months, but you know I’m confident we’ll get one. It turns out that 65% of financial advisors surveyed and 83% of their clients anticipate a recession. That’s up from 49% and 63%, respectively, six months prior. It seems as if more and more people are coming over to my way of thinking. If the financial advisors do not buy stocks out of concern of a coming recession, that depressed demand will act to keep prices low, dampening the likelihood of outsized returns in 2020, which means I’ll be more likely to take profits if it looks as if we’ve gotten a blow-off top in the stock market. The stock market’s major indices have certainly been outpacing the growth of earnings, which are on track to drop 1.1% this quarter for S&P 500 companies even as the index is hitting new highs. That’s worrisome, but not so worrisome to suggest much more short-term risk of anything other than a normal dip in prices.

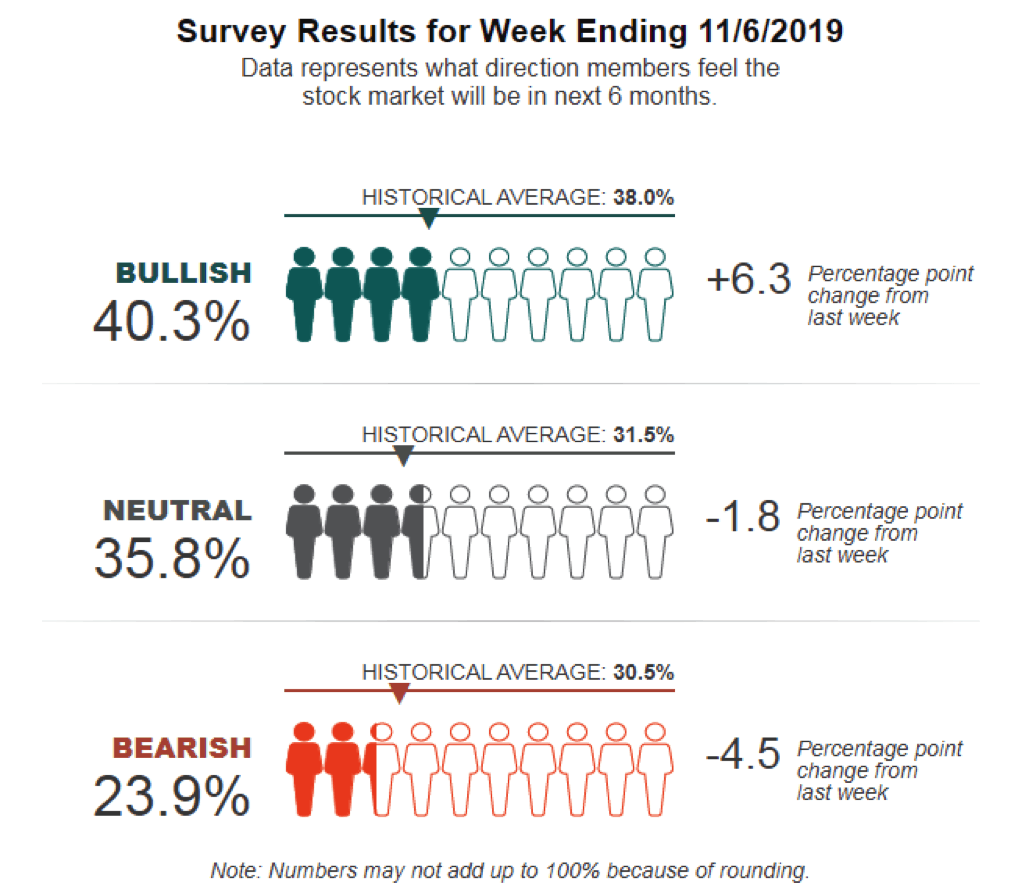

It’ll be hard for the market to keep up the pace of the last month and accelerate meaningfully from these levels without a bigger dip. Not that we need a dip to get higher stock prices. A slower grind upward is the more likely path than quick returns from here. Though, given increased positive sentiment, investors may very well expect those quick returns to keep coming. New highs in the stock market have boosted investor confidence, per the American Association of Individual Investors survey.

Over the last month, as stocks have moved up, investor bullishness has nearly doubled. A month ago, with bullish sentiment lower, it was a contrarian signal that there was a good chance of good returns. And we got them. Similarly, bearishness has unwound and been cut nearly in half. A month ago, it too gave a contrarian signal that the market would move up. But now the mood is more neutral. Any dip we get from here would probably be small given that bullishness is currently only a bit above its historical average. But I’m not holding out for continued rapid returns. With only a couple months left in the year, there were only nine weeks so far in 2019 when bullish sentiment was above average bullish readings. It’s hard to imagine the stock market sustaining high levels of bullishness as we approach heated political dialogue, a slide in corporate earnings and the concern of a possible recession. A big enough surge in investor optimism would cause a contrarian like myself to confidently act smarter than the average bear (or bull, as the case may be), and get more defensive in investment portfolios. I’ll watch that for you, and let you know what to do.

–––––––––––––

Allen Harris, the author of ‘Build It, Sell It, Profit: Taking Care of Business Today to Get Top Dollar When You Retire,’ is a Certified Value Growth Advisor and Certified Exit Planning Advisor for business owners. He is the owner of Berkshire Money Management in Dalton, managing investments of more than $400 million. His forecasts and opinions are purely his own. None of the information presented here should be construed as individualized investment advice, an endorsement of Berkshire Money Management or a solicitation to become a client of Berkshire Money Management. Direct inquiries to aharris@berkshiremm.com.

This article originally appeared in The Berkshire Edge on November 13, 2019.

Allen is the CEO and Chief Investment Officer at Berkshire Money Management and the author of Don’t Run Out of Money in Retirement: How to Increase Income, Reduce Taxes, and Keep More of What is Yours. Over the years, he has helped hundreds of families achieve their “why” in good times and bad.

As a Certified Exit Planning Advisor, Certified Value Builder, Certified Value Growth Advisor, and Certified Business Valuation Specialist, Allen guides business owners through the process of growing and selling or transferring their established companies. Allen writes about business strategy in the Berkshire Eagle and at 10001hours.com.