How to save money with tax-gain harvesting

Tax-gain harvesting is an opportunity to convert a long-term taxable gain into a potentially tax-free cost basis.

Readers are probably familiar with tax-loss harvesting. Tax-loss harvesting is a form of tax planning. It’s the process of selling some investments at a loss, usually to offset gains you’ve realized when selling other assets at a profit. The losses can offset the gains, thereby reducing your tax bill.

As the owner of a financial advisory firm (Berkshire Money Management), tax-loss selling is not an unfamiliar practice to me. Not only do I appreciate it because it reduces tax obligations, but I like it because it’s easy. I don’t have to coordinate schedules and confer with the client or the client’s accountant.

I don’t have to confer with the client because, well, I am hired to do tax-smart things, so I’ve got the go-ahead to pull the trigger when applicable. And I don’t have to consult with the client’s accountant because tax-loss harvesting can theoretically benefit investors no matter what. Even if the investor doesn’t have capital gains to offset that year, the losses can be carried forward to offset future gains and ordinary income.

Tax-loss harvesting is easy to do. During the tax year, you want to offset gains, sell investments in taxable accounts that have unrealized losses. You must adhere to the IRS’ “wash-sale rule.” The wash-sale rule says you cannot buy back the same, nor a substantially similar investment, for 30 days or else you lose the tax benefit.

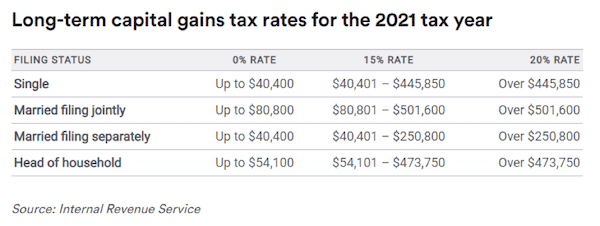

Tax-gain harvesting targets selling investments with gains instead of selling assets with losses. Tax-gain harvesting allows you to pay zero tax on capital gains in some years and pay fewer overall taxes in future years. You will want to work with your accountant to determine just how much of a gain you should take in a tax year. As you are aware, we have a tiered federal income tax rate in the U.S. The concept is similar for capital gains.

It’s not as if realizing a bit more profit would be the worst thing possible. However, taking the maximum amount of gains would be more beneficial for this strategy. Tax-loss harvesting can be done year-round, however, tax-gain harvesting is best implemented at year-end, so that your accountant can make the most accurate calculations.

Tax-gain harvesting lets investors realize long-term capital gains with little or no impact now and potentially significant tax savings later. The strategy is particularly effective if you fall into a lower tax bracket during the harvest year. Perhaps you were temporarily unemployed, or your company had a bad year, or you deferred a bonus, or you haven’t yet started drawing required distributions from your individual retirement account (IRA). Not that your income must be higher in a later year. However, if you suspect your adjusted gross income (AGI) will become larger, then you should feel a bit more compelled to talk to your accountant about tax-gain harvesting opportunities.

As illustrated in the chart, if you are married and filing separately, you pay zero on capital gains if you earn up to $80,800 of AGI. Then the rate bumps up to 15% or 20%, depending on the increase of your AGI.

Suppose that your tax status is married filing jointly, and your accountant calculates that your AGI will be $70,800 for 2021. Under that circumstance, you could sell enough of an investment to realize a long-term capital gain of $10,000 and not have to pay taxes on it. Let’s walk through this. Let’s say that a couple of years ago, you purchased $5,000 of Disney stock, and now it’s worth $15,000. That’s a $10,000 gain. Because your $70,800 AGI is ten thousand dollars below the $80,800 threshold, you can realize all of that gain and not pay a cent on capital gains taxes.

But wait! There’s more! Let’s say that you’re a big Disney fan and you want to continue holding the stock. Well, in that case, you can immediately repurchase the stock — you sell it for $15,000, then use those proceeds to buy back $15,000 worth of Disney stock. Fast-forward a couple of years later, and your investment dream came true — your Disney stock is now worth $30,000, and you decide to sell it.

Because you sold it and rebought it, your cost basis increased from $5,000 (your initial investment) to $15,000 (your repurchase price). Because of the increased cost basis, your taxable gain shrunk by $10,000 ($30,000 – $15,000 cost basis = $15,000 gain, vs. $30,000–$5,000 cost basis = $25,000 gain).

Suppose your AGI was $100,000, in the middle bracket, when you sold the Disney stock that second time. Your long-term capital gains tax rate would be 15% (it’ll probably be higher in the years ahead, but let’s stick with the current rates). The reduced taxable gain would save you $1,500 ($10,000 x 15% = $1,500).

A quick caveat. Capital gains, even when taxed at 0%, can still increase your AGI. An increased AGI could result in reducing or disallowing certain things like medical expense deductions. So be sure that your accountant investigates how this one lever may affect others.

Claiming gains in the correct year can reduce your taxes in future years. Using an investment approach that pays attention to taxes helps you keep more of what you earn.

Allen Harris is the owner of Berkshire Money Management in Dalton, Mass., managing investments of more than $500 million. Unless specifically identified as original research or data-gathering, some or all of the data cited is attributable to third-party sources. Unless stated otherwise, any mention of specific securities or investments is for illustrative purposes only. Adviser’s clients may or may not hold the securities discussed in their portfolios. Adviser makes no representations that any of the securities discussed have been or will be profitable. Full disclosures. Direct inquiries: [email protected].

This article originally appeared in The Berkshire Edge on October 11, 2021.

Allen is the CEO and Chief Investment Officer at Berkshire Money Management and the author of Don’t Run Out of Money in Retirement: How to Increase Income, Reduce Taxes, and Keep More of What is Yours. Over the years, he has helped hundreds of families achieve their “why” in good times and bad.

As a Certified Exit Planning Advisor, Certified Value Builder, Certified Value Growth Advisor, and Certified Business Valuation Specialist, Allen guides business owners through the process of growing and selling or transferring their established companies. Allen writes about business strategy in the Berkshire Eagle and at 10001hours.com.